THIS ALL-WHEEL-DRIVE FAT BIKE IS BUILT TO CROSS CONTINENTS

We cover a lot of bikes – road bikes, gravel bikes, the occasional mountain bike – but it’s fair to say we’ve never written about a bike quite like this. That’s because this bike, and the expeditions it is built for, are well outside the ordinary.

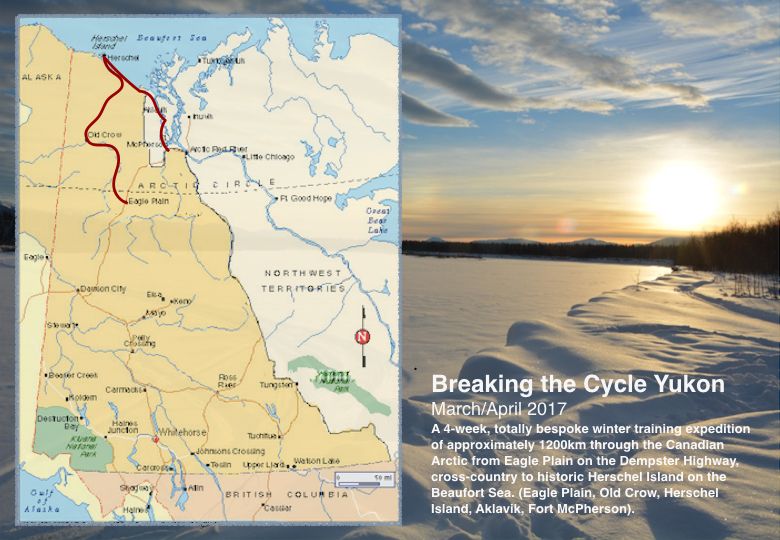

Kate Leeming, a Melbourne-based adventurer who owns this Christini fat bike (and four others), has spent the better part of three decades exploring the world by bicycle, tackling increasingly arduous and mindblowing challenges. The ultimate goal – something Leeming has been working toward for a number of years – is to perform the first crossing of Antarctica by bicycle. To prepare, Leeming has tested herself, and her gear, against similar conditions to what she’ll face in the Antarctic by riding in Svalbard, Greenland, Iceland and four weeks in far-northern Canada.

It would be reductive to infer that she’s just a snow and ice specialist (although she is that, too). In 2010, she became the first person to cycle the line from Senegal to Somalia, Africa’s most westerly point to its most easterly. That 20-country, 22,000 kilometre (13,670 mile) odyssey was a ride with a purpose, highlighting the challenging conditions facing some of the most impoverished nations on earth. “People thought I was going to die out there,” Leeming says, “but I mitigated all the risks,” including traversing conflict-torn Somalia with an armoured guard.

In 2019, Leeming returned to Africa, cycling 1,621 km (1,007 miles) on sand, along Namibia’s Skeleton Coast into a howling headwind. And at other points in her life as a two-wheeled explorer, Leeming has cycled 13,400 km (8,320 miles) across the width of Russia – she is the first woman to achieve this feat – and 25,000 km (15,530 miles) around Australia, including 7,000 km (4,350 miles) of extremely rough, remote terrain.

When we caught up in mid-2020 in a gap between lockdowns, Leeming had recently returned from a COVID-aborted plan to ride the length of the Andes. That trip would have culminated in an attempt to reach – by bicycle – the summit of Ojos del Salado, the world’s highest volcano and South America’s second highest mountain at just shy of 7,000 metres. Instead, Leeming tells me, it ended with an expensive, stressful scramble to get the last flight out of La Paz, Bolivia before the continent shut down.

We’re here to talk about a bike, but I think it’s important to lay those foundations to explain the conditions this unique machine is designed to conquer, and the singular mindset of its rider, who amongst other things is also a real tennis professional, an author, an educator, and an inspiration.

So: this is an all-wheel-drive fat bike designed for crossing continents, being ridden by a woman who’s already cycled on six of them.

All-wheel-drive?

Leeming has a fleet of five fat bikes designed by Steve Christini, a Philadelphian manufacturer who developed the first prototype of an all-wheel-drive mountain bike way back in 1995. In the years since, Christini has refined the concept, entering into production in 2001, and eventually expanding his business into the motorcycle industry in 2007. Today, that’s where the majority of Christini’s attention lies.

When Leeming was on the hunt for a suitable bike for her Antarctic expedition, she was put onto Steve Christini’s design by another frame builder, and they began working together. “It was very difficult to track Steve down,” Leeming told me. “We’ve never met face to face – it’s all just been discussions and emails and that’s it. So there’s a lot of trust in our relationship. He just loved the challenge of putting his technology into a bike to go across Antarctica.”

At the core of the design is a shaft-drive system that runs from the rear wheel through the frame, to the head tube, and down a leg of the fork to the front hub.

A handlebar-mounted switch – the ‘clutch’ of the system – controls whether the all-wheel-drive is engaged or not. When it is, the spiral gear at the rear wheel locks into the driveshaft and instantaneously engages the front wheel if there is any loss of traction at the rear wheel. Likewise, if there’s any loss of traction at the front wheel, it is re-engaged.

The system promises impressive descending capabilities, with Christini saying that “with the front wheel under power, it is nearly impossible to wash out the front end.” It also climbs well and has remarkable traction on sketchy surfaces like ice, snow and sand, which is what drew Leeming to the design in the first place.

In total, the system adds a claimed 1.3 lbs (~0.6 kg) to the bike, which, for the type of boundary-pushing terrain that Leeming routinely tackles, makes it a “no-brainer”.

“It’s all a shaft drive system, and so the drive angles are absolutely critical to make it flow smoothly,” Leeming says. “So it’s quite a feat every time. [Christini] is making little tweaks, and some things in the last two bikes are really amazingly smooth.”

Each of the five bikes Christini has built for Leeming have specific purposes. The first design – the one that “made the dream possible” – was what Kate brought to Svalbard for her initial testing for the planned Antarctica expedition. “It looks beautiful, but he couldn’t get it to hold anything wider than a four-inch (101.6 mm) tyre on the back and the flotation is by far the most important thing in this,” Leeming says. “The system worked, but the bike needed wider tyres and a couple of tweaks.

“The second one was made for northeast Greenland, and by this stage, Steve was able to build a bike around 4.8-inch (122 mm) wide tires,” Leeming continues. That bike, with its wider tyre clearance, is what Leeming now uses for her sand expeditions. Versions three and four of Christini’s design are optimised for polar conditions, allowing for up to 5.05 inch (128 mm) tyres – Vee Tire Co’s Snowshoe 2XL, the widest fat bike tyre currently on the market.

Bike number five – the white Christini bike pictured here, which was used on Leeming’s recent Andean expedition – is built for narrower tyres, with tweaks for better manners on smoother surfaces and mounts for bags for an unsupported stretch in the middle of the expedition.

Parts picked to last

While each of Leeming’s five Christini fat bikes are slightly different in their design, there are a number of commonalities throughout them. After countless thousands of kilometres spent riding, Leeming has a wealth of experience to draw on when deciding what will work for her unique demands, and what won’t.

“I choose a bike and the parts by where I’m going,” Leeming says. “I’m looking for design, reliability, for whatever conditions I’m dealing with. And you have to think about what the worst conditions are.”

The parts list is informed to a certain extent by what is available to her through the brands that support her, but is also carefully chosen to last.

Gearing is SRAM’s GX Eagle groupset, a single-chainring setup with a colossal 500% spread. “I asked for a big gear because I’m going up some big mountains,” Leeming says with a laugh. “I need to keep going as much as I can, and at the other end [of the gearing range] I can cruise along. I’m not racing and it’s just about being consistent and with those tires, they’re as fast as they can be and still have that much grip.”

The other parts are a mix of brands, offering reliable options. Leeming uses Shimano XT SPD pedals, with the tension backed off. “I like to be clipped in, but not too tight – that’s almost caused a few crashes in the snow,” she explains to me. Her saddle of choice is a Selle Italia Diva – “I’ve got four or five of them” – atop a Thomson Elite aluminium seatpost.

Things are a little more surprising at the cockpit, with real-world experience informing the selections. Rather than an aluminium handlebar, Leeming opts for a carbon fibre RaceFace bar with ergonomically shaped Ergon grips. This particular combination was chosen not for its weight or any traditional performance metrics, but by how it handles cold weather.

The Ergon grips are rubber, which means they’re “warmer in extreme cold, and comfortable, and I like having bar ends for a change of position.” As for the carbon bar: “Carbon’s good also in the cold just because it doesn’t harbour as much cold as aluminium,” Leeming explains. “There’s quite a difference, actually. Fat bike number three, that went to the Yukon when it was seriously cold – down around minus 20 to minus 30, so it was a good test – you could feel the cold radiating off the aluminium bar.”

For this expedition, Leeming was rolling on Vee Tire Co’s T-Fatty in a 27.5″ x 3.25″ (82.6 mm) width, mounted tubeless to Sun Ringlé rims. Braking was courtesy of Avid’s BB7_MTN mechanical disc brakes, rather than a hydraulic system.

While Leeming acknowledges that hydraulic brakes offer better performance, there’s something to be said for the simplicity and serviceability of a mechanical brake, especially if you’re days away from a town, let alone a bike shop, in the middle of the Andes. “I know [these brakes] are a bit fiddly and a bit annoying, but if something goes wrong, you can still kind of fix them,” Leeming explains. “With hydraulics there’s just too much that could go wrong. I took that choice ages ago.”

Leeming has ridden mechanical disc brakes on all of her expeditions since her Australian journey in 2004. She illustrates her ‘simplicity first’ mentality with an anecdote from 1993, when, pre-disc brake and pre-internet, she wore through and split a rim in the muddy wilds of Siberia while crossing the newly formed Russia, raising funds for the survivors of Chernobyl.

That necessitated the local police to help save the day, with a spare wheel finally making its way to Leeming via a 200 km drive to Moscow, a four-hour flight across Russia, and a 120 km train ride. Four days later, Leeming was eventually able to continue her journey.

“Ever since then, I’ve just gone for mechanical simplicity, because I might be in remote places,” she says. “I’m mitigating risks all the time, and usually I can’t carry extra stuff if I’m unsupported. I’ve already got enough weight.”

On the South American expedition, Leeming – who is a meticulous planner – knew that there would be a stretch of a couple of days without a support vehicle, so she got Christini to add mounts for a rack and took a number of bikepacking bags too. That stretch, at an altitude of around 4,000 metres near Lake Titicaca, was a series of climbs – “down 300 metres, up 300 metres” – on sometimes rough terrain. It was, Leeming confirms, pretty hard going.

“The bike was really heavy,” she says, and it twinged a longstanding knee injury, exacerbated by Leeming competing at the Real Tennis Australian Open in January (she won both the singles and doubles title in 1996). With the stress of pulling together the expedition and sponsorship, Leeming arrived in South America a little short on condition and managing knee pain.

But – as is so often the case in life – cycling makes things better. Just before Leeming’s Andean adventure had to be curtailed by a hasty dash home, the injury started coming good and Leeming was riding herself into form. “By the time I got to La Paz, I realised for the first time in so long, I was actually walking down stairs without pain,” she tells me. “Cycling’s good for me, but I have very damaged knees that I have to manage. I don’t have massive power; I just have to use my gears cleverly. But it’s amazing what you can do.”

A few months after her aborted attempt to conquer the Andes, and to try to ride as high as anyone has ridden before, you can sense a desire to get back there and to finish the job. And after that, just one continent remains unconquered – Leeming’s biggest challenge and the only one that remains elusive. Antarctica.

Behind all of these expeditions is a steely will, and Leeming’s desire to fill in the gaps in the map and in her understanding of those spaces.

“I love to use the bike to explore the world, to understand better how it fits together,” Leeming tells me. “To get that feeling where you just understand. Where you bring your line on a map to life.”

Find out more

Kate Leeming is the author of Njinga and Out There and Back. There are a number of films and documentaries of her expeditions, with the most recent – Diamonds in the Sand, a film about her Namibian ride – nearing completion. She is currently in the process of securing funding for her attempt to be the first person to cycle across Antarctica.

You can find out more about Leeming and the educational modules she has developed based on her adventures at www.breakingthecycle.education.